Recently my mother and I attended a talk by Christo in an open lecture at Hong Kong University. It was inspiring to hear how, as well as his successes, this man found pride in failure, as well. In this post, I’m going to give a quick summary of what we learnt, and some additional thoughts. I quote from Christo throughout.

The purpose of the talk was to present the Mastaba Project, ongoing in Abu Dhabi, and the Floating Piers at Lake Iseo, Italy, completed last year.

Christo in his studio with a drawing of his Mastaba project (Source: http://www.thenational.ae/)

For the first few minutes, however, Christo ran us through a selection of his projects. While Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s first official piece was completed in 1960, Christo focused on their major, later, artworks. The “Wrapped Coast” in Sydney in 1969 was the first high-profile wrapping project and carried a strong environmental message that resonated with audiences worldwide. Since, Christo and Jeanne-Claude have wrapped valleys (“Valley Curtain”, 1972), borders (“Running Fence”, 1976), bridges (“The Pont Neuf Wrapped”, 1985) and trees (“Wrapped Trees”, 1998).

Just beautiful: Christo’s naturally backlit “Wrapped Trees” (Source: http://christojeanneclaude.net/projects/wrapped-trees)

The primary medium of the wrapping project, cloth, is striking. The bright colours combined with the artificial forms of wrapped fabric create a sense of the surreal, arousing curiosity. For decades, audiences have been drawn to interact with Christo’s artworks both physically and psychologically. Part of the art’s appeal, perhaps, is that despite its contemporary application, cloth is a very traditional medium, having been painted on, used, and represented throughout art history. It obscures detail, drawing attention to form and scale. Where people’s attention often fixes on the minute, Christo’s art draws it back to the fundamentals and the big picture.

A truly enthusiastic speaker … in the end, the organisers had to rush him out of the lecture hall to get him to the airport on time! (for a 3-minute video of his presentation, click here!)

Of especial importance to Christo is that, unlike traditional sculpture, fabric moves. Its dynamic nature makes it tactile and sensual, almost “screaming for freedom”. He fled Bulgaria so that he could be an artist, so that he could be free. His projects are temporary and last only weeks, further conveying themes of motion and transition.

AMBITION

Christo’s website declares that it is

it is totally idiotic to call Christo and Jeanne-Claude the “wrapping artists.” [1]

I wholeheartedly agree. Christo’s work spans many materials and magnitudes. A commonality is better found in extreme ambitiousness, right from the very beginning.

The current Mastaba project draws inspiration from Christo’s early “Iron Curtain” sculpture. Commissioned in 1962, the wall of rusting oil barrels shut down a busy but narrow Parisian street, symbolising broken diplomacy during the Cold War. It was a brave move at the time. Politically ambitious, it can be argued that the “Iron Curtain” launched Christo into the sphere of public awareness, enabling future projects.

The Mastaba project, also to be built out of oil barrels, will, for lack of a better word, be monumental. 410,000 barrels will be placed in the middle of the Arabian desert, outstripping the height of the Great Pyramid and sprawling over a greater area than the Vatican City Plaza. What impressed me most was not, however, the scale, but the difficulty of realising the project. The sculpture is based on the shape of ancient Egyptian burial chambers[2], but the stability of those ancient structures does not guarantee that of Christo’s. The initial design would collapse under its own weight. It required several teams of top university engineering professors – who, in a humorous twist, weren’t told that they were competing with other teams – to solve what was proving to be a massive problem.

The engineer’s solutions to the “Mastaba challenge”: flatten the project and hollow it out!

The best solution was to flatten the project, making the mastaba shape hollow rather than solid. This has practical benefits too, which will allow the eventual artwork to be erected in ten days (-> click here for a computer simulation of the project).

Aiming high, Christo succeeded, demonstrating remarkable fearlessness, particularly as the Mastaba is not an isolated case. Many other of Christo’s projects faced technical challenges, to overcome some of which required the development of entirely new structural and material techniques.

PERSEVERANCE

The Mastaba is Christo’s longest-running project, conceived in 1977 and only granted permission for recently. It will be built in the Arabian desert, a homage to Arabic culture and a dramatic statement of human ability. This achievement comes at a cost. Christo’s projects often take thirty years or more to realise (a lovely representation can be found here), which, in his words, gives them “maturity” and “complexity”.

When asked what keeps him going, Christo waved off suggestions such as “courage”, claiming the word was too “pompous”. Rather, it’s love. Love for art, and for Jeanne-Claude. The first relationship began early; Christo had an art-filled childhood. Encouraged by his mother, he received tuition and a traditional arts education. Yet, after four years of liberal art school dabbling in drawing, sculpting, designing, and dreaming, Christo remained undecided. All these fields appealed to him, so he took the combination and made it his own. The amalgam of skills is present in all Christo’s projects, which leak from art into urban planning, architecture, and graphic design (the first critic of the wrapped Reichstag was an architect!) Even now, aged 81, Christo happily admits to being undecided. He simply loves art, and the precise form it takes is largely irrelevant.

Christo’s art centres around a desire to create something. Anything. My favourite quote from the lecture is

Art is totally rational, and totally useless!

Art does not have to serve a purpose, Christo seems to be saying, it simply has to be, and to be possible. I feel I understand what he means. There’s something that keeps all of us thinking about and reimagining and reshaping our world. I believe all people, whether they consider themselves artists or not, share it. Every time we imagine “what if?” we step into a rushing creative flow, and experience the same love for expressing ourselves, the same addiction to lay bare our thoughts to the world around us. Artists simply let their thoughts take concrete form; I firmly believe that anyone can, therefore, be an artist.

The difference between most of us and Christo is much greater. Expressing himself requires combining raw drive with amazing perseverance. The same perseverance that allowed him and Jeanne-Claude to, for years, earn a living off oil paintings also allowed him to fight through rejection after rejection (of 59 proposed projects, only 23 have ever been permitted). It is love for art itself that keeps Christo going, powering the perseverance that turns his dreams into reality.

Still, you can have dreams and grit without end, but without money, it’s unlikely anything will happen. I found Christo’s solution to funding his art as intriguing as amusing. He “exploits the capitalist system to its limits”, essentially selling art to make more. I was thrilled to see this system at work during Art Basel, where drawings of his umbrella project were being exhibited.

PROCESS: LAKE ISEO

Something that’s hard to find on the internet is the behind-the-scenes story of Christo’s sculptures. Told part of one that evening, I’ll try to relate what we learnt.

Floating Piers (2014/16) Source: http://www.christojeanneclaude.net/projects/the-floating-piers

Christo’s ideas come from all over the place, but the crux of his art is location. Many of his works are in areas of personal, artistic or historical importance. The Pont Neuf bridge is in Paris, where Christo and Jeanne-Claude met, a city of personal significance. It was also the first bridge without houses, making it an incredibly popular subject for artists for centuries. Christo also emphasised that, as his art is designed to be experienced by humans, it needs a reference point, preferably artificial, to demonstrate scale.

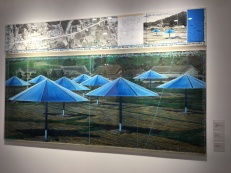

Sometimes, location gives his projects their meaning. An essential part of the “Running Fence” project, which started at the Californian coast, was that it crossed a highway. Highways are a crucial part of California’s identity, and the chosen one’s distance to the coast ultimately determined the scale of the project. The appearance of a project is also be affected. “The Pont Neuf Wrapped” used golden, silky fabric to represent the bridge’s heritage, as well as to match the unique Lutetian limestone of Paris, used in many of its buildings. “The Umbrellas” are yellow on the Californian coast and blue on the Japanese coast to represent their respective climates.

Location was key to the Lake Iseo project as well. The “Floating Pier”, a bright orange walkway floating freely on the lake, connected Monte Iseo (a small village accessible only by boat) to the mainland. The next step is what Christo calls the “software”, or journey, of a project. This is subdivided into visual brainstorming and interacting with people, who try either to “help, or stop” him. Like his sculptures, Christo’s concept drawings are temporary, visions rather than recordings. For this reason, he never draws a finished project from life. When exhibited, the illustrations are presented as slices of a larger journey, accompanied alongside over 500 pieces of photography and other evidence. While the final product is a powerful, “once in a lifetime experience”, the exhibitions provide insight into the long-term effort of its realisation. For Christo, it is often the permissions process that decides the personality of a project. The climactic weeks of the artwork’s actual existence are comparatively fast-paced and energetic, what with matters of rent, security, etc. Christo reflects that he oftentimes feels

more relief when it’s over than sadness!

Making a vision physically possible, the “hardware” part, is equally. To test the “Floating Pier”, Christo’s team selected a secluded lake near the German-Danish border. Engineers made detailed measurements of the forces on the pier, comparing them to the conditions on Lake Iseo. The final pontoons were built out of HDPE plastic blocks measuring 50x50cm, and filled with air. To provide a tactile experience, they were patterned to replicate woven fabric, then covered with 10mm thick, bright orange felt. Connected by enormous, dynamic screws, they allowed people to feel the motion of the water. Many, therefore, walked barefoot over the pier, or lay down on its sloped edge as though on a beach. Making the blocks was an immense task. Four factories worked worldwide to produce 220,000 cubes.

The Lake Iseo project was a huge success. 1.5 million[3] visitors flocked to Christo’s pier, to wander on it day and night. The true achievement, however, cannot be found in these statistics. It’s found in the documentary evidence, in the journey. A lot of art, especially fine art, is appreciated for its aesthetic alone. I, too, often find myself guilty of this. Because Christo emphasises his journey as much, if not more than, the final product, we come to appreciate it, enjoying the story. Perhaps all art should be seen in a similar way. After all, every painting has a story, every sculpture a history. A shift in this direction is underway. At Art Basel and Art Central this year, I found that many gallery owners were eager to talk about the art behind the scenes. One artist even just stained large sheets of fabric. Visually undramatic, the art lay in the time he had invested in hand making his paint, and coating his canvas layer by layer. It fascinated me. Undeniably, by reuniting art with its process, Christo has redefined how we look at contemporary works.

ENVIRONMENT

Christo’s projects leave dramatic impressions on us. In contrast, his massive projects leave little effect on the environment. All materials, which in the amounts used are quite valuable, are recycled. “The Gates”, which made up 5000 tonnes, the equivalent of 2/3 of the Eiffel tower, of steel, were sold to a Chinese manufacturer. The HDPE cubes used on Lake Iseo were recycled, and the lights used to illuminate the pier at night worked on solar power. The same applies to all Jeanne-Claude and Christo’s projects, which greatly impressed me. It just goes to show that, no matter how big you are, there’s always something you can do. After all, if art is “totally rational, and totally useless”, it shouldn’t harm anyone, either.

Before attending the lecture, I was not wholly convinced by Christo’s art. Listening to him tell his stories, however, in a quaintly disorganised and passionate style, gave me a much greater appreciation not only for his work but for him as a person. He showed me that perseverance in the face of repeated failure is crucial and that one should never be afraid to aim high. Given enough passion, it’s possible to wrap up any project.

Natasha

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Christo. “Floating Piers 2014 -16 Lake Iseo, Italy and work in progress Mastaba project for Abu Dhabi, UAE.” HKU Public Lecture Series, 23 March 2017, Graduate House, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong. Lecture.

[1] Jeanne-Claude. “Life and Work.” N.p., n.d. Web. 11 June 2017.

[2] “Mastaba | Archaeology.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 June 2017.

[3] “Christo’s Floating Piers on Lake Iseo Attract 1.5m Visitors – Corriere.it.” N.p., n.d. Web. 12 June 2017.